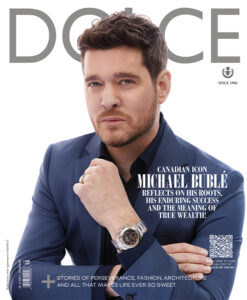

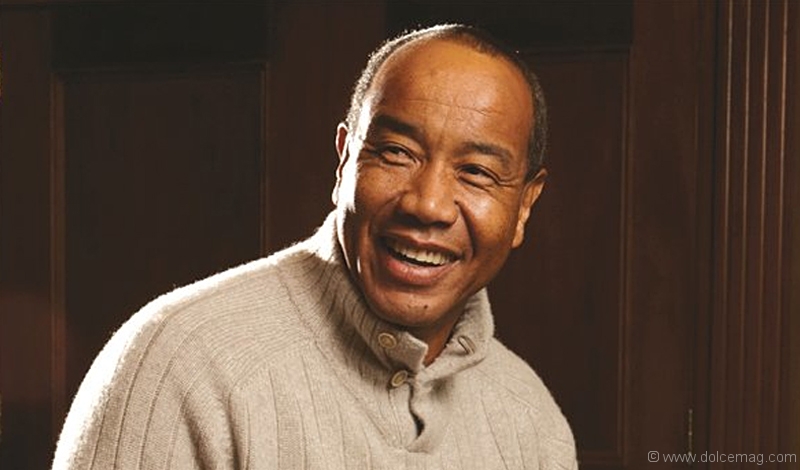

Michael Lee-Chin: Renaissance Man

Nothing about Michael Lee-Chin is ordinary. Even his style of philanthropy heralds a certain unceremonious swagger that contradicts nearly every element of the Canadian archetype. From his conspicuous dress code to his private jet penchant and fearless life philosophies, the Jamaican-born founder of Portland Holdings Inc. threw a splash of water on the face of Canadian business when he walked on the scene in the pre-digital ’80s. “He’s much more of an extrovert and much more socially engaged. He has an appetite for society and that kind of role than the sort of traditional class of philanthropists in Canada that maybe like to be all-too invisible at times,” says William Thorsell, former director and CEO of the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). “He can take a crowd and have them in his hands in minutes.”

This room-rousing gift most recently manifested itself at The University of the West Indies Benefit Gala on March 26, 2011, where Lee-Chin was being awarded alongside Canada’s former governor general Michaëlle Jean and Olympic champion Donovan Bailey for his contributions to Canadian and Caribbean communities. It was early evening and hundreds of top educators, entrepreneurs, politicians and even our best-known environmentalist awaited the arrival of the night’s honourees in the candlelit VIP section of Toronto’s Four Seasons Hotel. When Lee-Chin entered the room to the live vibrations of a grand piano sporting a black bow tie and dress shirt with crystal cufflink buttons, there was a palpable change in climate.

Seconds after unleashing his famed Cheshire cat grin, suits and gowns surround him as if he were the neighbourhood ice cream truck on a sizzling summer day. Any observing cocktail server could see how Lee-Chin’s cosmopolitan charisma could carry him to the top, but it’s only when speaking to him privately that you realize how unshaken he is. “To me, being honoured is a continuation of my aspiration to be a role model in my society, in my community, to give hope that anyone, irrespective of where you are starting from, can accomplish whatever your goals are,” says the silver-tongued 60-year-old, courteously repeating my name throughout the conversation.

When we meet the following week on a rainy Thursday morning at Portland Holdings Inc. in Burlington, Ont., Lee-Chin looks leisurely in a crème cashmere sweater and sandy beige slacks. Upon entering the privately held investment company’s mighty headquarters, you instantly get a sense of the amalgamation of work and play that’s become a cornerstone of his persona. From the capacious glass foyer that features a tropical koi pond with waterfall, to the bronze “Polar Bear and Cub” sculpture by Winnipeg artist Leo Mol, and “The Fisherman” painting by Jamaican artist Barrington Watson, it becomes clear that I am walking in Lee-Chin’s wonderland. “If you don’t have passion for what you’re doing, you should get out of what it is you’re doing. Conversely, if you have passion, then work isn’t work,” he says, settling into a time-worn armchair in a regally embellished room.

Though Lee-Chin appears at home in his corporate castle, undercurrents of his modest beginnings are ubiquitous. “I never forget where I’m coming from, and I don’t want to,” he says. Mark Strutt, who was hired by Lee-Chin in 1995 as a full-time artist-in-residence, seconds this sentiment. Strutt, who produced more than 60 paintings during his seven-year tenure, evokes a distinct memory of when Lee-Chin’s roots were poignantly apparent. “One time he found a photograph in a newspaper that reminded him of when he was a child. It was an image of a little boy climbing into an old galvanized water drum. He asked me to do a painting based on that because he said, ‘When I was a little guy, there was no hot water.’” The art-washed walls whisper intimate details of Lee-Chin’s life.

Growing up in the tiny town of Port Antonio, Jamaica, little Lee-Chin was raised by his teenage-orphan mother, Hyacinth, who worked three jobs to support them, including one as a bookkeeper at a high-end hotel owned by a member of Canada’s esteemed Weston family. “She set standards, very high standards, and not only that but she led by example. So saying is one thing, but acting it out every day, every minute, is another,” he says, of his No. 1 role model. When Lee-Chin was seven, Hyacinth married Vincent Chen, who had a son of his own before having seven children with Hyacinth. Since his family didn’t have the resources to send him to university, Lee-Chin got a job as a bellhop on a cruise ship, and then as a lab technician at a bauxite aluminum plant to save enough money for his first-year tuition. He applied to the engineering program at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. with a back-up plan of buying a Triumph TR7 convertible top if he wasn’t accepted. “I still haven’t bought my Triumph,” he jokes.

After a successful year as a civil engineer freshman, Lee-Chin had to figure out a way to summon the money for a second term. When scholarship requests were overlooked and laying sod on the campus landscaping team for the summer only brought in $600, he chose to do something bold. He wrote a letter to the prime minister of Jamaica, who at the time was Hugh Lawson Shearer. “I decided to take the bull by the horns: ‘Sir, it’s not reasonable to expect to be able to harvest if you don’t sow,’” he recalls writing. Shearer responded, telling him to stop by the next time he’s in Jamaica, and Lee-Chin optimistically spent $400 of his slim savings on a two-way plane ticket. The bull statue that sits on the table behind him suddenly becomes significant. He presented his marks to Shearer’s permanent secretary, and flew back to Canada with more funds than he initially dreamed of. “They gave me a scholarship, not for $2,000, but for $5,000 – per year for the next three years. So I had excess money that I was able to remit back to my family to help them,” he says, telling the story with wide-eyed enthusiasm.

This experience taught the then-20-year-old a lot about taking risks, validating the famous phrase, “ask and you shall receive.” Not long after graduating, Lee-Chin was seduced by the financial services sector and started selling products on behalf of a company called Mackenzie Financial Corp. When he spotted an opportunity to purchase company stock, Lee-Chin fused the same intrepid approach he used to get his tuition dollars (with a few new salesman skills) to convince Continental Bank of Canada (now HSBC) to lend him half a million dollars. It worked. “So I bought Mackenzie in the summer of 1983 at the equivalent price of $1 per share.” Four years later, the price rose to $7 per share and his initial $500,000 turned into $3.5 million. And that was just the beginning.

Lee-Chin swiftly became a force in the investment world, mastering the art of maximizing returns. “You can’t avoid risk, you mitigate risk, and in this case, my investment philosophy has always been [to] buy things you understand,” he says. AIC Limited was another company he evidently understood, and in 1987, he acquired the mutual fund firm which not only put him on the map, but also on Forbes’ “World’s Billionaires” list for several consecutive years. Though the company went from less than $1 million in assets to amassing more than $15 billion under his leadership at its apex, the recession had its repercussions and Lee-Chin made a tough decision to sell in 2009. As the towering six-foot-four titan of Portland Holdings Inc., his company now owns a bevy of major businesses here and abroad that span from the National Commercial Bank Jamaica Limited and Columbus Communications Inc., to CVM Communications Group and Medical Associates Limited.

Today, he’s a father of five and one of Canada’s most benevolent businessmen whose numerous endeavours include the indelible $30 million gift to the ROM, $10 million donation to the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto and $3.7 million towards Hyacinth Chen School of Nursing in Jamaica. “Mike is one of the most generous persons I know,” says G. Raymond Chang, fellow philanthropist, friend and director of wealth management firm CI Financial Corp. Lee-Chin met Chang more than 40 years ago and often takes his pal on jaunts for both business and pleasure on his private jet and helicopter. “He has a big heart, and I’m not referring to his public gifts. I’ve seen him open his home to a friend with terminal cancer for an extended period. He has also never forgotten his Jamaican grounding,” adds Chang.

Even the artist who was commissioned by Lee-Chin back in ’95 considers himself lucky to have met the mutual fund magnate. Strutt still vividly recalls the first time he walked into Lee-Chin’s office carting a sampling of his realist oil works. “Right away he wanted to buy some … He asked me why I was selling them for so cheap and I said, ‘well you know, who am I? I’m not a famous painter,’ and he said, ‘well, if there’s anything else I can do for you let me know.’” Little did Lee-Chin realize that his simple gesture would launch Strutt’s career and lead to a near decade-long bond. “Imagine seven years of just painting and not having to worry about anything else. Not many painters have that. It gave me time to master my craft and it gave me an income to feed my family,” says Strutt, who has since garnered enough acclaim to fulfill his long-time dream of opening an art gallery in his hometown of Hamilton. “I can’t say enough nice things. Mike is happy, charming, impeccable, warm … He’s a very multi-dimensional person – you can talk to him on any subject.”

It’s not surprising then, that Lee-Chin’s affection for the arts flowed into the palms of the ROM. Before making that massive $30 million commitment back in 2003, he had a pivotal heart-to-heart with Ontario’s former lieutenant-governor and Renaissance ROM campaign chair Hilary M. Weston. During the exchange, Lee-Chin asked Weston – whose family name has become synonymous with philanthropy – why she wanted him to be the primary benefactor. Her response is what sold him. “I told him, ‘because you belong to a new generation of people who came from different parts of the world to settle in Canada, and you have had great success. You are an iconic figure and an example for future generations. My family represents history, but your family is about the future of Canada,’” says Weston. “That is why he agreed to donate $30 million to Renaissance ROM. He was only glad that I didn’t ask for more because he would have given it!” According to Thorsell, his donation went far beyond the establishment of the Michael Lee-Chin Crystal and Hyacinth Gloria Chen Crystal Court. “He really made a statement that this major institution belonged to everybody and everybody had a role in it, everybody was welcome there,” he says, adding that Lee-Chin was just as much a fundraiser as he was a fund giver, inspiring several other Canadian immigrants to follow suit.

A humble Lee-Chin admits to giving himself a proverbial pinch every day. The physically fit investor is acutely aware that his path was an improbable one, filled with more blessings than bumps. “I was born in an era that gave me an opportunity to own a pair of shoes. Had I been born 250 years ago, I would have been owned – I would have been a slave. So I’m very, very aware that my being here has many factors that I had nothing to do with. I’m also very, very aware that there are many people that were born the same day, who were born to parents not by their choice, who didn’t guide them, who didn’t make them confident, in towns and cities and countries that immediately put them at a disadvantage,” says Lee-Chin, who was awarded the Order of Jamaica in 2008.

So there’s a reason why Lee-Chin is so extroverted; why he opts for a couture coat over an invisibility cloak; why he isn’t shy to give speeches and share his story. “I just want my life to be an inspiration to everybody who aspires,” he says. For fear of complacency and subsequent failure, he never forgets the bullish outlook and boyish aspirations that brought him here. Instead of following a conventional paint-by-numbers plan, Lee-Chin coloured outside the lines, proving that being an anomaly is far more fulfilling than being ordinary. www.portlandholdings.com

Rule of Three: Michael Lee-Chin

No. 1 Make sure that your attitude from the

get-go is that, ‘everything I do as a young person, I’m doing it with the eventual goal of building the most sensational legacy that I can.’ Start building that legacy from as soon as possible. Most people don’t think about legacy, so one should look at legacy as a work in progress and focus on, ‘What do I want for my legacy? What do I want to be known for 100 years from now? Or do I want to go by as a nobody? I didn’t add any value to society and I was just a number.’ Legacy is important.

No. 2 Secondly, passion: Be committed to a cause, because every great person is a disciple of a cause. Having a cause is what will have you bounce out of bed at 5:30 every morning and drop dead on your pillow at 11:30 every night and wake up and be enthusiastic and tap dance to work because you have a cause. Having a cause will give you passion. So when naysayers lash you, no problem, because your cause will give you passion, will give you commitment, it will enable you to persevere through whatever negatives or air pockets you may face – and you will face negatives and you will fall into air pockets.

No. 3 Have a belief system, have a strong value system. Live by your values. Values make decision-making very easy: black or white. And don’t be afraid to be bold! Most of us are too tepid. Don’t be afraid to be bold.

1 Comment

[…] magazine, many groundbreaking and inspiring figures have been featured. From Hilary Weston to Michael Lee-Chin, they all continue to remind us that living the good life means something different to everyone. […]