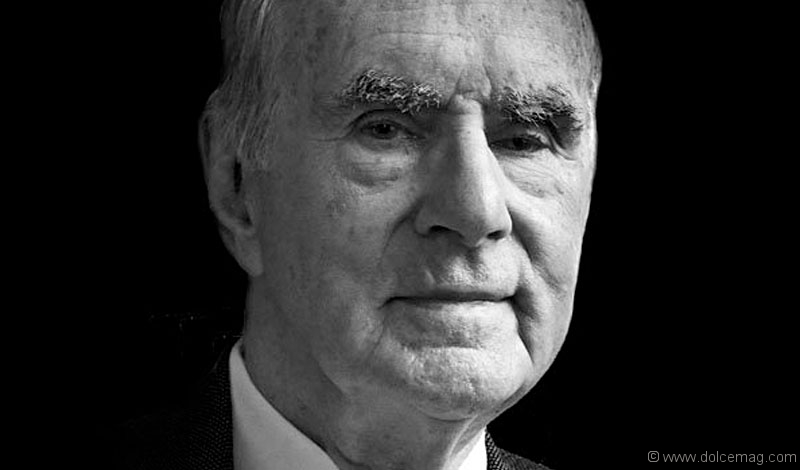

An Hour with the Honourable Hal Jackman

In an otherwise ordinary downtown Toronto office tower, the Hal Jackman Foundation’s 10th-floor University Avenue suite reaches a level of unlikely wonderment. A museum-like foyer where Persian rugs kiss chevron floors and landscape masterpieces coat the walls is just a prelude to the erstwhile lieutenant-governor of Ontario’s penchant for the arts.

The former chairman of investment and insurance holding firm E-L Financial Corporation Limited, whose name is habitually on Canada’s rich lists, seems unmoved by the sizable funds his business successes summoned. Since handing the empire’s reins to his own son, Duncan Jackman, the father of five and visitor at Massey College has become far more focused on inflating the fortune of others.

An archetype of civic commitment, the socio-political virtuoso has become a vociferous commentator on business, politics and public service — known to give his two cents, and then some. With a sonorous tone that speaks to attentive ears and an expression so storied you can’t help but attempt to read it, the Officer of the Order of Canada’s imposing presence is unparalleled. The hallway leading to his private quarters is lined with ghosts of Jackman’s past

— portraits so real you can feel their laser-like glare as you brush shoulders along the way. It’s there that the towering 80-year-old, who’s given more than $50 million to academic and arts-based causes, lowers into a salmon-coloured chair, crosses his arms and quietly awaits an overture of words.

You’ve had great success in business, but it’s fair to say you’ve become even better known for your commitment to public service. Your passion for the latter is apparent in everything you do. What sparked this philanthropic spirit?

I think part of it is your upbringing. You’re brought up in a family that was very committed to public service and charity, and both my mother and father were. It’s infectious, I guess, part of the genes maybe? Both my brothers and sister are very big in philanthropy, too, so it just comes on you. And the tax system is much better now than it used to be — it encourages philanthropy. In a sense, it gives a lot of people the option: do you want to pay taxes or do you want to give it away? For a lot of people, that’s an easy question. I’d rather give it to something I believe in than give it to the government, which might do anything with it. I’ve always given away every year, as far as I can remember, more than I’ve spent on myself and my family.

What other changes can be made to catalyze philanthropy?

Well they’re always pressing, I mean you can give stocks and be exempt from capital gains tax but they want to extend it to shares and private companies and real estate and they may be successful. I’m a little skeptical that they’ll get it now because I think that the rich, or the top people, are making way too much money in my opinion. I just don’t think, however it may be justified, it’s in the cards to lower the taxes for the very rich right now.

Your mother Mary Rowell Jackman was a devoted philanthropist. Did her charitable actions help engrain similar qualities within you?

I guess it did, we’re all products of past influences we’ve had. So our parents and the people we’ve known have an influence on us. It’s hard though for us to pinpoint this or that, but I think probably yes. My father too, he was excessively generous and relative to what he had he gave a lot of money, a lot of money and a lot of things.

What did you learn about life and business from your father, Harry Jackman, former Canadian politician and distinguished businessman?

I learned a lot of things. I’d say he had a very acute sense of judgment when it came to security values. He certainly encouraged my interest in politics, which I’ve always been interested in, and he was very generous.

Going back to the ’90s, what was your most memorable moment as the 25th lieutenant-governor of Ontario?

What I look back on most of all was that you were dealing constantly with volunteer effort. It could have been anything: building a new park, getting a fire engine for the volunteer fire brigade or building a wing in the hospital, something like that. So you always see the best of people because when they’re acting in a community sort of way to do something, collectively together, the problems they may have among themselves, I’d never see that. I’d never go to any bad meetings. I’d always kid to the premiers, [Mike] Harris and Bob Rae, they’d go to bad meetings, I’d never go to bad meetings.

Your most notable benefaction was a $30-million endowment to the University of Toronto in 2007, which made headlines as the largest commitment ever made by an individual to the humanities at a Canadian university. Why have you been so generous to U of T over the years?

Well that’s where I graduated from. I gave a lot of money to a lot of things up there but the big thing was $30 million to the humanities and $10 million — $11 million actually — to the law school. I graduated from the law school and it made me chancellor, and I was chancellor for six years. Now I’m visitor of Massey College, which I’ve also given money to. That’s my university. U of T has a huge advantage over the other colleges because it’s right in the centre of the city. It’s close to the banks, it’s close to the theatres, the opera, the ballet, the libraries, everything is within short walking distance to the University of Toronto, and the medical hospitals are all right there. So that makes a difference as to why the place is excellent — it attracts good people.

How does it feel to be in a position to be able to give back and have such a major impact on your city?

I don’t feel any different than I would if I didn’t. But I mean, you have to do something if you have some money. What do you do with it? What can you do? You’re going to die, and I’m an old man; you have to do something. Now I guess some people would have an apartment in Rome and Paris, a place in Florida and Palm Springs, I don’t have any of that. I don’t have it because it doesn’t appeal to me; it was not really a conscious decision to give to the humanities building or buy a place in Arizona. I never had that choice, it just never occurred to me. I love Canada, I love Toronto; I think it’s the greatest city in the world. I have a farm just outside here and that’s it. I don’t have any fancy place in any other country and I can’t understand these big salaries these guys make. I never made that.

You actually earned a reputation as Canada’s most underpaid CEO when you controlled E-L Financial Corporation Ltd. Why didn’t you take a bigger cut?

Yeah I was, well that’s what it was. There was this [feature] that ranks people that are underpaid relative to the size of their company, I guess, but some of them, how do they get to make $20 million? It’s absurd, obscene, I mean I wouldn’t know what to do to spend it, I couldn’t. I really couldn’t. I mean what do you do? You start to develop a lifestyle, I guess you could if you bought a house in the Hamptons or maybe in Toronto. You could get a huge palace out in Oakville or someplace, you could do it and then do it in different other cities. You could spend it and have a personal household staff of 20 or 30 people and chauffeur-driven cars and jet airplanes, you could spend it. But there’s no kick in that. I don’t understand it. With philanthropy, I don’t know that I’m that much more generous than anybody else, but there, it’s going to make a difference.

Do you believe in altruism?

I would get more kick, I think, out of my last big gift, which was $11 million to the [U of T] law school. I get a bigger kick out of that than buying a jet airplane, I can tell you that! Or a yacht. I can tell you this: particularly when you’re lieutenant-governor, you recognize so many people who give donations, and then as chancellor there were some very large major gifts when I was there and it’s amazing. I never met anybody who cried or wept about a gift. They’re all delighted. I’ve never seen anyone or any member of the family have a negative feeling about a gift.

What are some of the principles of the Hal Jackman Foundation?

The Hal Jackman Foundation, which is relatively small — it’s not small, it’s getting bigger — is basically run by my daughter Victoria. It’s almost exclusively the arts, creative arts, particularly visual arts, and she does a lot of stuff. But that’s hers, the rest [of the kids] are trustees, and if I have anything left they’ll get it.

Describe your current economic outlook. In the eye of the global financial crisis you were reasonably bullish and quite accurate in regards to Canada. What is your position today?

I think we’ll struggle through. Our government’s giving mixed signals, particularly in the United States. The Central Bank of Bernanke says we’re going to have quantitative easing, keep interest rates low, stimulate the economy, and banks have got to loan the money, meanwhile Hillary Clinton and others are saying the trouble with Americans is that they don’t save enough, they spend too much. Those are mixed signals, you see, those are inconsistent signals and I think that’s what’s spooking the economy. There’s a paralysis of leadership.

If you had a magic wand, what would you change?

I don’t have to do that — I’m an old guy, I’m retired so I don’t have to do that. I just sit back and think. And I stopped speculating. I’m not going to be prime minister of Canada, they’re not going to elect me.

Is there an average day for Hal Jackman?

I don’t race to get downtown early in the morning. It depends, leisurely I walk to the office for exercise; I live in Rosedale. I don’t do much. I talk to nice people like you, I have a lot of friends, we have lunch. There are lots of things to do in the city. I don’t really do any business.

What is the most meaningful gift you’ve ever received?

I’ve got a really nice family and five children and six grandchildren so that’s pretty good. When you’re older, things like that become more important.

Looking back on your life, what’s been the source of your sweetest moments?

I don’t know that I can say I’ve had a moment, but I have no regrets about anything I’ve done. I think I’d do it all the same.

MAJOR GIFTS BY HAL JACKMAN

The Jackman Humanities Building and the Jackman Humanities Institute at U of T $30 million

The U of T Faculty of Law $11 million

The Canadian Opera House Corporation $5 million

Canadian Opera Company $1 million

National Ballet Company $1 million

York University (Philosophy) $1 million

Massey College $1 million

Dictionary of Old English $500,000

Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies $300,000

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) $1 million

Photography by Christoph Strube

No Comment